Until risk management becomes common philanthropic practice, we will miss the boat on maximizing impact. Here’s how to start developing the policies and practices you need.

By Laurie Michaels & Judith Rodin posted on Stanford Social Innovation Review

There is a system failure in philanthropic practice that is diluting impact and costing funders potentially billions of dollars. The glitch? The absence of common risk-management practices as an integral part of the grantmaking process.

In its Summer 2016 issue, Stanford Social Innovation Review published an article by Open Road Alliance that highlighted this generally overlooked aspect of grantmaking, noting that there is little or no explicit and systematic preparation by donors for contingencies that might damage a project’s success.

In 2015, Open Road conducted a survey, the results of which made plain the extent of the cross-sector avoidance of discussions about risk. Out of 200 randomly selected donors surveyed, 76 percent reported that they did not ask potential grantees about possible risks to the project during the application process. Grantees reported that 87 percent of the applications they filled out did not ask for risk assessments. Why is this of such critical significance? Here’s why: Both funders and grantees surveyed estimated that one in every five grant-funded projects would encounter unexpected obstacles that derailed success.

What’s more, even though funders acknowledged that 20 percent of their projects would likely be negatively affected by unexpected events, only 17 percent of those funders reported that they set aside funds for such contingencies. In short, although funders and nonprofits agree that 20 percent of our potential social impact is at risk, as a sector, most do nothing about it.

To address this gap in philanthropic practice, we, as the founder of Open Road Alliance and the president of The Rockefeller Foundation, co-convened leaders from across the philanthropic sector to discuss practical methods for assessing and planning for risk. Composed of 25 members, the Commons is a geographically diverse group of practitioners including leaders of institutional and family foundations, law firms specializing in philanthropic governance and tax issues, financial advisory firms, and nonprofits of varying sizes and missions.

The Commons affirmed that the lack of open conversation about risk in philanthropy has a negative effect on funder-grantee trust and project impact. And through a six-month, consensus-driven process, with the support of Arabella Advisors, the group developed adoptable and adaptable policies for addressing risk and implementing risk-management procedures throughout the grantmaking value chain.

The Commons also developed a set of user-friendly risk-management tools that are applicable across the philanthropic sector and address issues that face funders of all sizes and types. (Recognizing the inherent power dynamic between funders and fund seekers, the Commons designed its first tool kit for funders, rather than for nonprofits, to use.) In this article, we offer a high-level look at the steps that a foundation might take to implement effective risk-management mind-sets and activities throughout its organization. The full set of policies and risk-management tools can be found at: http://openroadalliance.org/resource/toolkit/

Defining Risk

About 15 years ago, funders generally stated “impact” as their goal, without any standard definition or best practices for impact measurement. The word was widely used but poorly understood. As such, its usefulness for our sector was limited. Now, there is a consensus about the differences between output, outcome, and impact; the words have distinct meanings, and therefore they’re useful across the sector.

Today, we see “risk” in much the same way that impact was viewed 15 years ago. Many funders like to describe themselves as “risk taking,” but in the absence of a common definition and frameworks for best practices, these statements are difficult to evaluate at best, and meaningless at worst.

Risk does have a straightforward definition: It is the likelihood that an event will occur that will cause some type of undesirable effect. These events can occur anywhere, anytime. They may be predictable or not, controllable or not, and caused by internal or external variables. The concept of risk sits on a spectrum, and identical events may be deemed more or less risky based on the viewpoint of the funder.

Moreover, while labeling something as a risk often implies the possibility of a negative effect, taking that risk can be a profoundly positive choice. While the existence of risk is a given, the choices one makes in the face of that risk are inherently subjective. Herein, then, is the basis of a core definitional distinction that would be useful for funders: risk culture versus risk management.

Risk culture refers to the concept of risk as a subjective choice and reflects an organization’s appetite or tolerance for taking risks. Organizations that have thought through and codified the essential parameters that define their risk culture can bring internal and external clarity to the process by which they make choices regarding investments and grants.

In contrast, risk management is necessary to deal with the unavoidable existence of risk regardless of one’s appetite or tolerance for it. Risk management is concerned with the reduction or avoidance of disruptive events, as well as risk-mitigation strategies and contingency planning. In grantmaking, risk-management practices are the steps that funders and nonprofits can take to reduce either the likelihood of a harmful event or the harmful consequence of that event. In both risk culture and risk management, there is no such thing as zero risk.

Even with the distinction between risk culture and risk management, a discussion of risk can quickly become confusing when we consider what is at risk. To maintain clear terminology and to help funders compare and prioritize different types of risk, the Commons proposes the following risk taxonomy specific to the philanthropic sector:

- Financial risk.Financial risk refers to the risk of losing money. Funders are sensitive to threats to the foundation’s endowment and place a high value on protecting those investments. The Commons encourages funders to equally consider its programmatic dollars as investments where the return is measured in impact. This perspective inspires impact oriented questions, such as “How much money are we willing to risk to achieve impact?” or “In what scenarios would we rather risk losing money versus losing impact?” This also prompts funders to consider how to protect the impact of the dollars already spent—for example, with a supplemental grant.

- Reputational risk.Reputational risk stems from events that cause a foundation to experience an embarrassment or threat to its brand. Funder appetite for reputational risk varies, but funders with a commitment to learning from failures and sharing those learnings tend to be more open to reputational risk.

- Governance risk. Governance risk refers to events that could affect compliance with legal, tax, or good-governance practices, such as conflicts of interest, inappropriate organizational structures, and inexperienced or unqualified boards. As with financial or reputational risk, a funder should not take a governance risk without simultaneous steps to mitigate that risk.

- Impact risk. Impact risk, also called execution or implementation risk, refers to events that negatively affect the intended impact of a given project. To the Commons, this is a critical area of risk for philanthropy, as risks to impact are threats to our sector’s raison d’etre. Impact risk exists at the project level, the portfolio level, and the organizational level.

Evaluating and managing impact risk has been the primary focus of the work of the Commons, to date. Typically, it was also the type of risk that members had in mind when developing steps for implementing risk-management practices and strengthening risk culture throughout a foundation’s value chain—from its board to the nonprofits it supports.

Understanding Risk Culture and Management

A foundation’s board of directors or trustees has the primary responsibility with senior management to define and clarify the organization’s risk culture and profile. Just as a board sets an acceptable level of financial risk with respect to its endowment or other investments, the board should set broad parameters for taking risk within its grants portfolio.

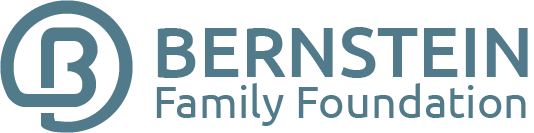

The accompanying chart offers a list of considerations and set of guiding questions designed to support a discussion that can help lead an organization to identify its risk profile. (See “Considerations Affecting Risk Appetite.”)

These discussions are likely to be lengthy, as the board examines hypothetical scenarios, clarifies the balance of risk versus impact, and looks at the record of unsuccessful projects in the process of developing a risk-profile statement that provides core guidance for staff and grantees. Additionally, by examining their past practices, funders can ascertain whether their grantmaking and investments align with their ideal risk profile.

Defining risk culture is value neutral. Being risk averse is not objectively better than risk taking, and vice versa. In a similar vein, while risk often carries a negative connotation, it can also be a positive or even necessary idea in the context of risk culture. For example, innovation is dependent upon taking risk, and it is axiomatic that greater risk can often bring outsized results. It is the board’s role and responsibility to give broad guidance to foundation staff regarding the acceptability of certain levels of risk.

While the board sets the course, the foundation’s president and executive team actively steer the ship on a day-to-day basis. It is therefore the role of the leadership team to translate the foundation’s risk-profile statement into common policy and practice. This is also where leaders can embrace risk as a pathway to learning, rather than approach it as a boogeyman to be avoided.

For the foundation to truly learn from risk and failure, its risk profile needs to become part of the organization’s daily culture. Yet, we know that building culture is easier said than done. To increase the chances of success with this endeavor, the Commons recommends going beyond paper statements to model the desired culture in an intentional and deliberate manner.

To live your risk culture, the Commons suggests holding regular conversations with staff members about risk and failure. Talk about the foundation’s core values, its risk appetite, and the right balance between risk and reward. Foundation leaders can get creative with the format and incentives aligned with such conversations.

For example, for many years, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation held an annual contest on the “Worst Grant” or the “Worst Strategy.” The intent was to create a new norm that embraced candid discussion about failure. While the contest outlived its usefulness,1 its spirit is still a part of the foundation’s culture of learning. From sharing evaluation results to hosting staff learning sessions on risk, the Hewlett Foundation aims to encourage dialogue about failures and missed opportunities in order to improve future outcomes.

Such approaches also begin to reframe conversations about failure to ones about learning. To this end, it may be helpful to evaluate a “failing” program in terms of how risk was managed. Rather than simply looking at outcomes, ask yourself, “Did we see this coming? If not, why not? What could we, as the funder, do to mitigate this risk in the future?”

Yet, when it comes to risk culture, internal conversation is not enough. In order to set expectations and help potential grantees to self-select, funders should communicate their risk culture externally. Consider posting your risk-profile statement on your website and including it in your request for proposals (RFPs) to help potential grantees and cofunders gain a better sense of whether your foundation is a good match for them.

Finally, be sure that other internal incentives, such as performance reviews, reflect the desired risk culture. Discuss risk management in annual performance conversations with staff members, and consider offering staff members incentives for taking smart risks, applying your risk profile to investment recommendations, exercising good use of contingency resources, and taking advantage of opportunities to learn from failure.

Even in the most conservative risk culture, risk will still always exist. Therefore, the work of the leadership team also involves setting policies and practices to mitigate the risk that is inherent in the everyday grantmaking process. In a comprehensive risk management approach, these procedures would affect everything from budgeting to applications, due diligence, and monitoring and evaluation (M&E) processes. Two of the most critical policy items are budgeting for contingency funding and incorporating risk management into the RFP process.2

Budgeting for Contingency Funding

It’s axiomatic that “risk minus cash equals crisis,”3 and so financial structures are critical to help funders budget realistically for risk. The Commons recommends that funders set aside contingency funding as part of their standard organizational and grant budgeting processes. Since risk is relative, the size and scale of a given foundation’s contingency resources will depend on its risk profile and therefore the kinds of projects in its grantmaking portfolio. To guide funders in determining the appropriate scope for contingency funding, the Commons recommends building policies off of the following factors:

- If your foundation is investing in projects that have a higher number of unknowns or variables that can affect impact, it will likely require more contingency resources than if you are investing in better-understood efforts with long track records where the risks are more overt, quantifiable, and less likely.

- Assess how much of your portfolio is made of high-, medium-, and low-risk investments. If your portfolio skews toward high-risk grants to startup organizations and first-time planning, experimental, or learning projects, then you may need to set aside more contingency resources than if you typically fund well-established organizations and proven projects.4

- Analyze your grantees’ financials. If your grantees tend to have less cash on hand and lower unrestricted net assets, then you will likely need a larger contingency fund. Conversely, nonprofits that are well funded with unrestricted assets may be able to cover their own emergencies through internal reserve funds.

- Poll your staff members to see how many contingency requests they received over the past year and the total dollar amount of those requests. Keep in mind that these figures may be artificially low if you have not historically had a policy or practice of contingency funding.

Consider, for example, The Rockefeller Foundation’s contingency budget structure. Here, the board and staff have created a flexible contingency budget structure in two ways. First, the board annually authorizes the president to go above the annual budget by as much as 5 percent to ensure the success of the foundation’s initiatives. This discretionary contingency fund allows the foundation to move quickly in order to support grantees and initiatives that may be facing unexpected obstacles. Second, by working within an initiative-based strategy, the board also approves multiyear initiative budgets, which allows Rockefeller’s executive team and CFO to manage the budgets in a portfolio rather than a grant docket approach. This enables the foundation staff to respond to unexpected needs and shift funds from one area to another.

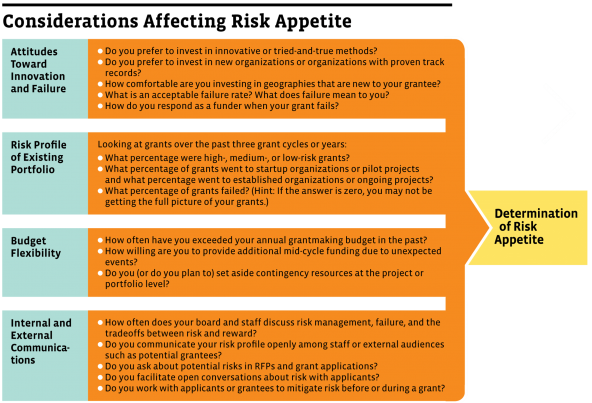

Other, smaller foundations have employed simpler contingency funds by a variety of methods, including setting aside a flat 10 percent in the budget for emergencies, creating a fast-acting executive committee that can make rapid decisions and release additional funds, or asking each grantee to budget for contingencies in its own grant applications. Whatever the amount and method, once you determine the size and scope of your contingency fund, you will also need to develop the funding criteria and decision-making protocols to get that money out the door when needed. (For a breakdown of these steps, see “How to Build Contingency Protocols.”)

Incorporating Risk Management into the RFP Process

Funders can help pave the way for more transparent exchanges with nonprofits about risk simply by including questions about risk in RFPs and grant-application forms. This step alone would represent major progress in planning for risk, since a staggering majority of funders do not ever ask what could go wrong that might require additional financial support. When funders do not ask, nonprofits do not tell because they fear that even raising the topic will jeopardize future funding.5

Sometimes, however, simply asking a nonprofit about risks that imperil impact does not generate enough useful information. The Commons recommends leading by example and starting the conversation by sharing the foundation’s own risk profile in RFP and application forms. By including a risk-profile statement in RFPs, funders can help potential grantees understand whether or not their work aligns with the foundation’s risk culture.

This risk-profile statement can be both broad and specific, including a description of your overall risk-appetite level as well as how that appetite may vary between specific program areas or portfolios. When crafting such statements, be deliberate in including the reasons and rationale of why you may have a low tolerance for one type of risk but a high tolerance for another. Remember that this culture side of risk is inherently subjective and that you’ll need to clearly explain your perspective.

A risk-profile statement can also touch on topics related to risk such as how you define “failure” within your grant portfolio. This can be a good place to provide historical data on the makeup of your program investment portfolio (for example, a percentage breakdown of high-, medium-, and low-risk grants, restricted versus unrestricted funding, and amount set aside for learning grants).

Once the topic is broached, funders can inquire about risk on the grantee side by including at least one risk-related question in the RFP. Asking such a question opens a channel for a transparent conversation about risk, and the applicant’s responses will help foundations assess whether a mutual fit exists. Possible questions that lend themselves to written responses include: What are the top three risks you may encounter during the course of this project, the steps you could take to mitigate these risks, and the ways in which we (as the funder) could help? What could happen to derail the intended impact of your project? What risks have you encountered implementing similar projects in the past, and how did you respond?

Both funders and nonprofits participating in the Commons’ work underscored the fear, uncertainty, and frustration that often permeate the application process—in which nonprofits may spend weeks writing an application, often followed by months of silence from the funder. In such a scenario, nonprofits acknowledge that they may not be fully forthcoming on a written application, even if the funder asks.

For this reason, it is important for funders to follow up the written application with a verbal discussion of risk with grant applicants. The program officer should be clear that the conversation is about risk mitigation and management, rather than a test for flaws. Sample questions that lend themselves to a productive in-person interaction include: When you consider this project, what worries keep you up at night? What obstacles do you foresee with project implementation? What could I do—either now or down the road—to help you mitigate risks to impact?

Lastly, reviewing a nonprofit’s financials is just as important for risk management and contingency planning as it is for due diligence. When reviewing financials from a risk-management perspective, there are a few approaches that can particularly help.

The first is to review any project or organizational budgets in the grantee’s original format. Understanding how the finances are organized by the grantee itself gives much better insight into a grantee’s financial acumen than having it populate a pre-made template.

Another risk-management approach is to review the balance sheet for assets and liabilities, specifically with an eye toward seeing the amount of unrestricted net assets held, as these assets are often the only source for nonprofits to provide their own contingency funds. Similarly, while most funders request budgets, many may not have insight into a grantee’s cash flow projections for the next 12 months.6 Looking at cash flows in addition to budgets or balance sheets is critical to assessing fundraising and spending trends. Understanding where a potential grantee may face cash flow crunches will allow you to better time your gift to avoid being the source of a crunch or to possibly alleviate anticipated shortfalls.

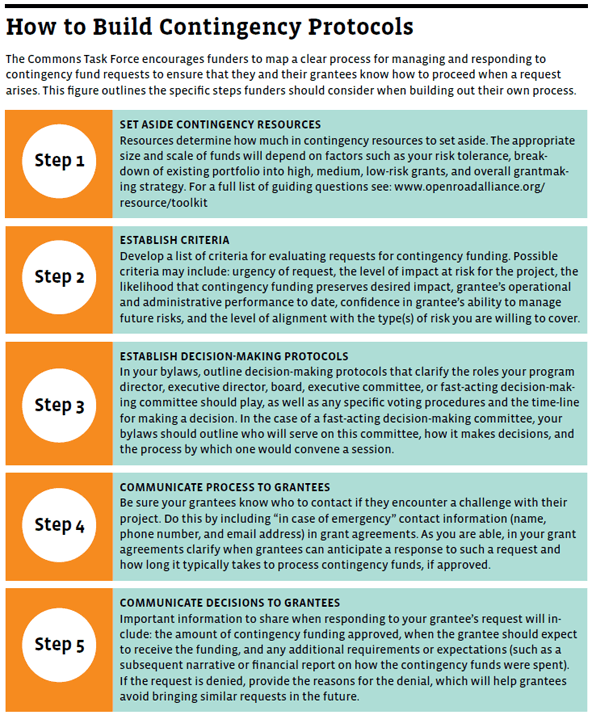

Once the application process is complete, steps similar to those outlined for an RFP process can be implemented for monitoring, evaluation, and reporting procedures. Like M&E, risk management is a continuous learning process that involves identifying, mitigating, planning for contingency, and then monitoring and reassessing risks as projects move forward. (See “The Risk Assessment Cycle.”)

In fact, funders should consider aligning their M&E processes with the level of risk anticipated for each portfolio or project. This would mean continuing to engage grantees in conversations about risk throughout project implementation and tailoring the frequency of these exchanges to align with anticipated risk.

The recoverable grants team at Open Road Alliance developed a Risk Scorecard to facilitate this process. The Risk Scorecard assesses individual grants across a range of roughly 30 pre-identified risk factors, which include balance sheet strength, liquidity, management quality, operating methodologies, country risk, and regulatory risk. Categories are weighted according to Open Road’s risk profile and preferences.

Based on qualitative and quantitative assessment, each recoverable grant is then assigned a “risk level category,” which determines the extent of monitoring and reporting that is required. For example, leaders of a project in the lowest-risk category would need only a 30-minute phone call with the portfolio manager once a quarter, whereas those heading up projects in the highest-risk category might be asked to submit monthly financials and accommodate an in-person site visit from the funder every quarter. During these check-ins, risk levels would be reassessed, and scores would be shared and discussed with grantees.

From application to final report, foundation leaders can set both the policy and the tone to make risk management a more regular and normative part of the grantmaking process.

Building Effective Funder-Grantee Relationships

While including risk in an application is a critical first step, the partnership between a funder and a nonprofit does not live on paper; it lives in relationships and is strengthened by the phone calls, e-mails, and site visits between program officers and nonprofits. Though it is not often thought of in policy terms, the Commons believes that ensuring transparent, honest, and effective communication between funder and grantee is both the hardest and highest form of risk management. To underscore this point, our survey research showed that only 52 percent of nonprofits feel comfortable discussing problems that occur mid-grant with a funder.

Funders can do much to foster an atmosphere that encourages nonprofits to be transparent about possible risks to impact by enabling their program officers to exercise greater discretion. In the tool kit, the Commons recommends some specific grantmaking practices that can help foster greater trust and transparency, such as increasing unrestricted funding, providing multiyear grants, and streamlining the application process for repeat or long-term grantees. However, in the case of funder-grantee communication, we recognize that there is no simple checklist or paper-based protocol that can get to the heart of building strong relationships.

Rather than considering such suggestions as mere policy changes, the Commons encourages funders to consider how they can allow the people closest to the action to meet their grantees’ needs more flexibly and thereby ensure and insure the intended impact of the grant. In some cases, creating the space for agency and flexibility will involve more change in culture than paper-practice. For example, one of the often-cited concerns of nonprofits participating in the Commons (and echoed by nonprofits in Open Road’s portfolio) is that funders “don’t truly understand” the context they are working in. It’s important to note that the nonprofits in question weren’t referring to a lack of policy knowledge or experience with a relevant regulatory framework. Rather, their comments are much more relational in nature and more akin to a perceived lack of empathy than just “understanding.”

To tackle this issue, funders can take steps proactively to understand the daily challenges of their grantees’ work. Funders can encourage staff to get involved with a nonprofit organization outside of their role as a funder. Experiencing “the other side” builds empathy and may better position funders to have open conversations about risk with grantees.

Finally, remember to approach all risk-management practices as a two-way conversation. Ask potential grantees to provide input to risk assessments, and give them an opportunity to review the assessments after completion. Without grantee input, mitigation strategies cannot be effectively considered or implemented.

Many of these suggestions don’t represent anything particularly new in the conversation about grantee-centric and partner-based approaches to philanthropy.7 To the Commons, however, these behaviors are not just “nice”; they’re necessary for comprehensive, effective risk management. Without partnership, funders have only a list of potential problems, not a path forward to solutions. Risk-management policies themselves are not enough. It is how they are used and communicated by frontline staff that determines how effective your risk-mitigation efforts will be.

What’s at Stake

Philanthropy in the United States is a $373 billion industry,8 and the absence of risk management results in lower impact per dollar spent. Roughly 61 percent of grant-funded projects that encounter obstacles and cannot access contingency funding end up reduced in scope or terminated, a percentage of waste that is unacceptably high.9 That represents nearly $43 billion in grant dollars per year that could have either no impact or less impact than originally planned. And this is far more than a policy discussion; when projects are terminated or reduced in scope, the people who depend on these programs lose vital services. Risk management in action preserves impact for vulnerable populations and ecosystems.

Philanthropy has evolved to insist on valuing and measuring impact, which makes it ripe for the next level of professionalization and sophistication. And current trends—in the quantification of impact and results-based financing—make the need for better risk management more pressing, even imperative. Within philanthropy, we are seeing unprecedented intergenerational wealth transfers,10 the creation of new philanthropic models, and a new generation of foundation leaders, all seeking to reimagine how we can most effectively achieve impact. There is a growing appreciation in the sector that funders must pursue a more explicit partnership between those who have the money and those who have the capacity to generate impact.

Meanwhile, inequality is growing, and financial markets are facing more uncertainty than ever before (if also their highest levels of profit). The lines between the private and nonprofit sectors are increasingly blurred, and external events continue to shape the barriers we face as impact seekers.

All these variables make the need for a robust discussion and practice of risk management imperative to our sector. We know that at least one in five philanthropic investments is affected by unpredictable variables. Until guidelines based on historical evidence and shared expertise are put in place, and until those guidelines lead to risk-management practices as a common philanthropic practice, we will miss the boat on maximizing impact. A stronger risk culture, and better risk management across our sector, will enable us to create greater impact and increase the effectiveness of every dollar deployed for social good.

Notes

1 June Wang, “Forgetting Failure,” Stanford SocialInnovation Review, March 22, 2016.

2 To review all seven tools related to risk management, please visit www.openroadalliance.org/risk

3 Clara Miller, “Risk Minus Cash Equals Crisis,” NCRP State of Philanthropy 2004.

4 Certain high-risk strategies, such as challenge grants or venture philanthropy models, may make the deliberate choice not to have contingency funds, as the purpose of the strategy is to fail fast.

5 Open Road Alliance Survey: 47 percent of grantees surveyed said they believed that asking for additional funds affected the likelihood of being awarded future grants.

6 Many nonprofits may not have cash flow projections as a preexisting report, and producing one could exceed the organization’s abilities or be an outsized burden. Funders should understand where their grantees sit and right-size their requests accordingly.

7 For more on the conversation about granteecentric philanthropy, see Peery Foundation, Grantmakers for Effective Organizations, The Whitman Institute, and others.

8 Donations from US individuals, estates, foundations, and corporations reached an estimated $373.25 billion in 2015; Giving USA Survey, 2015.

9 Drawn from ORA 2015 Survey on Risk in Philanthropy.

10 Over the next 30 to 40 years, $30 trillion in assets will be passed down in North America alone, according to Accenture’s report “The ‘Greater’ Wealth Transfer: Capitalizing on the Intergenerational Shift in Wealth.”